Unlocking Phytoplankton Metallomes with Comparative Analysis of Metal Quotas, Quantitative Proteomics, and Inferred Metalloproteomes

Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 50, 27367–27377: Graphical abstract

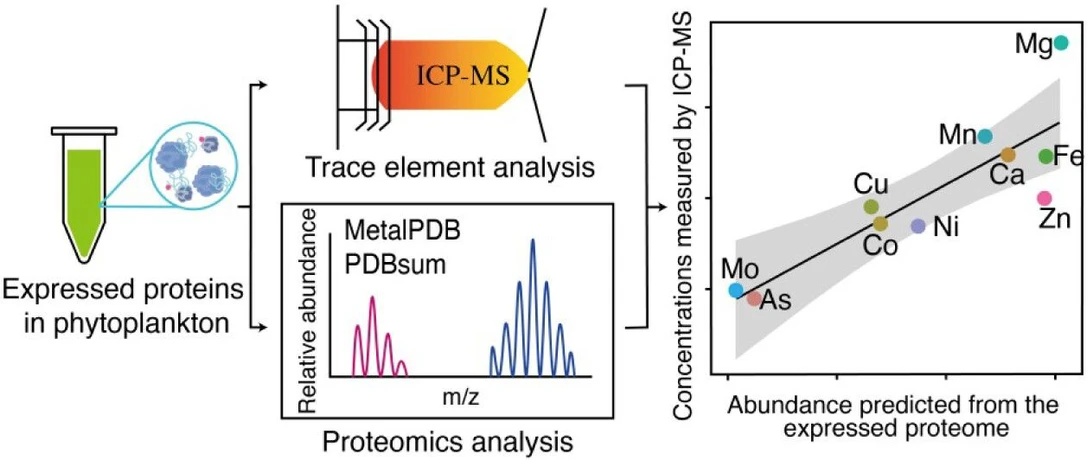

Metalloproteins play essential roles in marine phytoplankton, yet their metalloproteomes remain poorly characterized. This study combines protein modeling, quantitative proteomics, and ICP-MS measurements to assess metal requirements across several phytoplankton species, including chlorophytes, a haptophyte, and a cyanobacterium.

Results show strong agreement between proteome-inferred metal demands and measured cellular metal quotas, while providing deeper insight into biological functions. Mg-containing proteins were most abundant overall, with Zn, Fe, and Mn as dominant trace cofactors. Distinct differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic phytoplankton were observed, and strain-level analysis demonstrated how metalloproteomes reflect environmental adaptation and metal limitation strategies.

The original article

Unlocking Phytoplankton Metallomes with Comparative Analysis of Metal Quotas, Quantitative Proteomics, and Inferred Metalloproteomes

Qiong Zhang*, Jiayou Ge, Fengjie Liu, Shabaz Mohammed, Kedong Yin, and Rosalind E. M. Rickaby

Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 50, 27367–27377

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5c11233

licensed under CC-BY 4.0

Selected sections from the article follow. Formats and hyperlinks were adapted from the original.

Many important biological processes of phytoplankton, including photosynthesis, carbon fixation, and nitrogen reduction, rely on enzymes that have metals as cofactors. (1) It has been estimated that half of all enzymes must be associated with a particular metal to function. (2) The availability of metals in the environment has changed over geological time and, given imperfections in the selectivity of metal transport systems, proteins have evolved to make the best use of metals that are more available. (3−5) Depending on their evolutionary histories, different groups of marine phytoplankton may have differences in their metalloprotein compositions and metal transport strategies. The evolving trace metal availability in the environment, thus, may provide a selective pressure to promote the proliferation of different phytoplankton groups in the oceanic environment, affecting the phytoplankton community structure with knock-on effects on the marine food web and carbon sequestration. (5) It is crucial to understand the utilization of trace metals by different groups of marine phytoplankton that inhabit contrasting niches in the modern ocean, not only by assessing the accumulation of trace metals in cells but also examining the functions of trace metals in different biological pathways.

In previous studies, the utilization or requirements of trace metals by marine phytoplankton were mostly determined by measuring the elemental stoichiometry in cells (metallome or quota of trace metals). (6−8) In the field, attempts have also been made to investigate the elements in phytoplankton (9,10) which have then been compared with profiles in the abiotic environment to understand their relationships. (11) The discovery of various metal storage proteins and the plasticity in elemental quotas under different environmental conditions raise the question of whether intracellular trace metal quotas reflect true differences in trace metal usage by phytoplankton. (12,13) In the past few decades, more and more studies have focused on metal–protein partnerships, using approaches such as genome-wide analysis to identify homologues of known metalloproteins and other deduced metal-binding motifs encoded within sequenced genomes. (5,14) However, this approach has limitations in estimating metal abundance in cells because not all genes predicted in the genome would be translated and expressed as proteins under all environments, and a single gene for a metalloprotein could be highly expressed, such that a translation from genetic presence to a required concentration is not linear and could be environment-dependent. To obtain in situ metal abundance in metalloproteins in cells, native separation of proteins by HPLC or PAGE followed by the detection of metals using ICP-MS (15,16) has been used. This approach also has limitations in that, without bioinformatics, it cannot identify the function of proteins within which the metals are found, and it may also depend on the composition of the media to which the organism has been exposed and in which it has been growing. An ideal way to solve the problem would be to separate and purify each of the proteins and then identify both the associated metal (e.g., by ICP-MS) and the protein sequence (e.g., by mass spectrometry). However, this approach is constrained by the resolution of chromatographic or electrophoretic techniques, making it challenging to establish the metal–protein associations unambiguously; many proteins often co-occur in metal-containing fractions. Additionally, this method requires huge volumes of biomass and is both time-consuming and complex, complicating the reconstruction of the expressed metalloproteome in cells. The techniques and challenges for metalloproteomics have been discussed in detail in previously published review articles (and the references therein). (17)

In this study, we determined the trace metal utilization (the metallome) of different phytoplankton from their expressed proteome via a protein modeling and homologue identification approach, and then compared the resulting metallome with the metal quota data measured by the traditional inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). This approach allows the building of a link between the truly used trace elements and their biological functions in phytoplankton. We aim to fill the gap between an estimation of metals encoded in the genome and metal analysis by ICP-MS in phytoplankton, which may be more broadly applicable to infer cellular metallomes.

Materials and Methods

ICP-MS Analysis

All preparation of samples for ICP-MS measurement was undertaken using trace metal clean methods. All plasticware used in this study, including culture flasks, pipette tips, and centrifuge tubes, was precleaned in 10% quartz-distilled HCl and thoroughly rinsed with 18 MΩ cm water in a clean laboratory. Trace elements in the filtered lysates of G. huxleyi (OA1, OA4, OA8, OA15, OA16, OA23, and RCC 1242) and Synechocystis (FACHB898) strains were measured using an ICP-MS. The detailed ICP-MS method and instrumental settings are described in Zhang et al. (2018). (31)

Protein Mass Spectrometry

The peptides were resuspended in 5% formic acid and 5% DMSO prior to mass spectrometry. They were separated on an Ultimate 3000 UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and electrosprayed directly into a Q-Exactive Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) through an EASY-Spray nanoelectrospray ion source (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The peptides were trapped on a C18 PepMap100 precolumn (300 μm i.d. × 5 mm, 100 Å, Thermo Fisher Scientific) using solvent A (0.1% formic acid in water) at a pressure of 500 bar. The peptides were separated on an in-house packed analytical column (75 μm i.d. × 50 cm packed with ReproSil-Pur 120 C18-AQ, 1.9 μm, 120 Å, Dr. Maisch GmbH) using a linear gradient (length: 65 min, 15% to 35% solvent B [0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile], flow rate: 200 nL/min). The raw data were acquired on the mass spectrometer in a data-dependent mode (DDA). Full scan MS spectra were acquired in the Orbitrap (scan range 350–1500 m/z, resolution 70000, AGC target 3e6, maximum injection time 50 ms). After the MS scans, the 10 most intense peaks were selected for HCD fragmentation at 30% of normalized collision energy. HCD spectra were also acquired in the Orbitrap (resolution 17500, AGC target 5e4, maximum injection time 120 ms, isolation window 1.5 m/z) with the first fixed mass at 180 m/z. Charge exclusion was selected for unassigned and 1+ ions. The dynamic exclusion was set to 20 s.

Results and Discussion

Trace Elements Determined from the Expressed Proteomes of Different Phytoplankton

Based on the expressed proteome sequences, we predicted metal-binding proteins and compared their distribution among various phytoplankton species (Figure 2). The inference revealed 28 different metals in G. huxleyi, 31 different metals in C. reinhardtii, and 30 different metals in Synechocystis. Although only 6 different metals were identified in O. tauri proteins, it has to be noted that the analysis for O. tauri was only based on the 40 most abundant proteins reported in this organism (21) and, hence, the listed elements, including Mg, Fe, Mn, Ca, Zn, and Cu, may represent the most essential metals for the species.

Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 50, 27367–27377: Figure 2. The number of metal-binding proteins identified in the expressed proteome of the haptophyte G. huxleyi (a), the chlorophyte C. reinhardtii (b) and O. tauri(c), and the cyanobacteria Synechocystis (d). Pie charts show the percentages of metalloproteins containing specific metals. Original proteome data for G. huxleyi are from Mckew et al. (2013) (24) for C. reinhardtii are from Hsieh et al. (2013) (77) for O.tauriare from Martin et al. (2012) (21) for Synechocystisare from Chen et al. (2018). (22) *Noted that for O. tauri, only the 40 most abundant proteins were included in this analysis. ND: no metal binding was found in the proteins.

Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 50, 27367–27377: Figure 2. The number of metal-binding proteins identified in the expressed proteome of the haptophyte G. huxleyi (a), the chlorophyte C. reinhardtii (b) and O. tauri(c), and the cyanobacteria Synechocystis (d). Pie charts show the percentages of metalloproteins containing specific metals. Original proteome data for G. huxleyi are from Mckew et al. (2013) (24) for C. reinhardtii are from Hsieh et al. (2013) (77) for O.tauriare from Martin et al. (2012) (21) for Synechocystisare from Chen et al. (2018). (22) *Noted that for O. tauri, only the 40 most abundant proteins were included in this analysis. ND: no metal binding was found in the proteins.

The number of proteins that bind with different metals varies dramatically in phytoplankton. For metalloproteins, there are variations in the binding affinities of different metals to organic molecules. For example, the affinities of divalent metals to proteins have a tendency to follow a universal order of preference, namely the Irving-Williams series (Mg2+ and Ca2+ [weakest binding] < Mn2+ < Fe2+ < Co2+ < Ni2+ < Cu2+ > Zn2+). (43) Cells can simultaneously contain proteins having high-affinity-binding metals, such as Cu and Zn, and others that require uncompetitive metals, such as Mg and Ca. One of the least competitive metals for binding with biological chelators, Mg, is even found to be the most widely distributed metal in the metalloproteomes of various phytoplankton species in this study, supporting the observations of high concentrations in the protein fraction of cells (at millimolar concentrations (31)).

In all phytoplankton species in our analysis, the Mg-containing proteins are found to have the highest proportion in all metalloproteins identified. About 30% of the metalloproteins in different strains of phytoplankton are found to contain Mg or depend on it for function (Figure 2), suggesting the important role of Mg in phytoplankton cells. It is generally coordinated in protein complexes by ATP or ADP and has also been found to be largely distributed in the chloroplasts or thylakoids in G. huxleyi and Synechocystis. (22,24) The essential roles of Mg in plants have been reported in various studies. Mg2+ is known to be the central atom of the chlorophyll molecule, and its levels in the chloroplast regulate the activity of key photosynthetic enzymes. (44) It was reported that approximately 15–35% of total Mg is in the chloroplasts of a plant, (45) and it also serves as an osmotically active ion in the regulation of cells (46)

Comparison Between Metallome Measured Directly and Reconstructed from Proteins

A large proportion of metals, such as Fe, Mn, and Cu, are found in membrane proteins,and may contribute significantly to total cellular quotas. (54,55) However, for method development purpose, we endeavored to remove the cell membranes from our samples to focus mostly on the analysis of intracellular metal quotas and metalloproteins in the cytosol fraction in this study. We note that our analysis includes some membrane-bound proteins likely derived from organelles or surface membranes disrupted during sonication.

The derivation of cellular metal composition, as determined by two different methods, is compared in Figure 3. The abundance of metal in the proteins is determined as the relative abundance of the protein multiplied by the number of metal ions needed for the specific protein. The abundance of the proteins was normalized to ensure that the total intensities from each replicate measurement for the same species were similar. Since the proteomic data used here were generated from different studies using different instruments, we cannot quantify or compare the absolute biomass of proteins used for each species. Therefore, we cannot compare the absolute trace metal abundance between species solely from metal inferences of expressed proteomes. Nevertheless, we can estimate the relative abundance of different metals in the same species. For the elements that are both measured by the ICP-MS and identified in the proteome, there are generally good correlations (r2 = 0.81 in Figure 3a and r2 = 0.74 in Figure 3b) between the two approaches. This indicates that the metal compositions determined from the protein modeling may be reliable and, therefore, can reflect the metal usage in different phytoplankton. This would provide a level of assurance to further investigate the metal binding associated with various proteins, thereby deepening our understanding of the roles that different metals play in phytoplankton.

Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 50, 27367–27377: Figure 3. Relationship between the abundance of metals determined by ICP-MS analysis (normalized to C, mmol/mol C) and metal abundance determined from the metalloproteome analysis (the unit is arbitrary). To account for strain variations, the ICP-MS data for the cellular metal content of G. huxleyi are average values from 7 G. huxleyi strains isolated from different areas of the ocean, and the proteome-derived metal composition data are average values calculated from 2 of those G. huxleyi strains (OA1 and OA16) isolated previously, and data from Mckew et al., 2013. (24) The ICP-MS data for Synechocystis are from Synechocystis sp. FACHB898 measured in this study, and the proteome data are calculated from Chen et al., 2018. (22) Noted that the abundance of metals from each proteome was calculated by using the metal stoichiometry multiplied by the relative abundance of proteins, which provides only a relative relationship of different trace metals, not absolute abundance. The symbols represent the mean values, and the error bars indicate standard deviations.

Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 50, 27367–27377: Figure 3. Relationship between the abundance of metals determined by ICP-MS analysis (normalized to C, mmol/mol C) and metal abundance determined from the metalloproteome analysis (the unit is arbitrary). To account for strain variations, the ICP-MS data for the cellular metal content of G. huxleyi are average values from 7 G. huxleyi strains isolated from different areas of the ocean, and the proteome-derived metal composition data are average values calculated from 2 of those G. huxleyi strains (OA1 and OA16) isolated previously, and data from Mckew et al., 2013. (24) The ICP-MS data for Synechocystis are from Synechocystis sp. FACHB898 measured in this study, and the proteome data are calculated from Chen et al., 2018. (22) Noted that the abundance of metals from each proteome was calculated by using the metal stoichiometry multiplied by the relative abundance of proteins, which provides only a relative relationship of different trace metals, not absolute abundance. The symbols represent the mean values, and the error bars indicate standard deviations.

Compared to the other metals investigated in this study, Ca and Mg appear to have a much higher relative abundance in the ICP-MS analysis than in the proteomic analysis of G. huxleyi and Synechocystis (Figure 3). These two elements are essential macronutrients for phytoplankton and plants. Ca is the most prominent secondary messenger that plays a crucial role in response to extracellular stimuli in all eukaryotes. Ca2+ fluxes are transported via Ca channels and transporters, such as Ca-ATPase, regulating a series of important biological functions, including mineral uptake and utilization, K+ homeostasis adjustment, and regulatory network activity in response to P or N deficiency. (56) Ca is not always incorporated into protein structures. The Ca abundance determined from the proteins in this study, therefore, is much lower than the actual Ca needed intracellularly. Similarly, the intracellular Mg2+ and K+ abundances should also be higher than those determined from the protein structures. Free Mg2+ and K+ are known to regulate cation–anion balance and serve as osmotically active ions in the regulation of cells (46) but free metal ion concentrations cannot be determined through the approach used in this study. Thus, it is not surprising to see much higher relative abundances of Ca and Mg in ICP-MS analysis than in proteomic analysis (Figure 3).