Exposure of black soldier fly larvae to microplastics of various sizes and shapes: Ingestion and egestion dynamics and kinetics

Waste Management, 203, 2025, 114852: Graphical abstract

Black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae are increasingly used to valorize food waste, but such substrates may contain microplastics from packaging. This study examined how microplastic size and shape influence ingestion and egestion during larval waste bioconversion.

Larvae were exposed to fluorescent polyethylene microplastics of different sizes and morphologies for 10 days. While microplastics did not affect larval growth or accumulate in the gut, ingestion strongly depended on particle size, with particles larger than 100 µm rarely ingested. Smaller particles were efficiently eliminated, with more than 90% removed after a three-day starvation period. A kinetic model was developed to describe microplastic uptake and elimination dynamics across particle size distributions.

The original article

Exposure of black soldier fly larvae to microplastics of various sizes and shapes: Ingestion and egestion dynamics and kinetics

Christelle Planche, Siebe Lievens, Tom Van der Donck, Jason Sicard, Mik Van Der Borght

Waste Management, 203, 2025, 114852

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2025.114852

licensed under CC-BY 4.0

Selected sections from the article follow. Formats and hyperlinks were adapted from the original.

Several studies have revealed that microplastics (plastic particles < 5 mm) can have various adverse effects on the environment and living organisms, including humans (Chen et al., 2023, Fournier et al., 2023, Lu et al., 2022, Osman et al., 2023, Wang et al., 2021). Microplastics can release toxic additives and monomers to the organisms or biota and act as carriers of various harmful adsorbed contaminants including heavy metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) (Godoy et al., 2019, Golwala et al., 2021, Zhang et al., 2022). The concentration of pollutants accumulated on microplastics can be 6 – 70 times higher than that of the surrounding environment (Golwala et al., 2021). Given the widespread contamination of microplastics in our food waste streams and the wider environment, it is important when using food waste streams as a substrate for the industrial production of BSF larvae to ensure that the presence of microplastics does not impact larval growth and survival, and above all does not compromise the safety of the larvae as feed ingredient for fish, chickens or pigs. Recent studies have shown that BSF larvae are not affected in terms of growth performance, survival, and bioconversion by the presence of polyvinylchloride (PVC) microplastics up to a mass fraction of 5 % in their substrates (Lievens et al., 2022a). Further research questions arise as the ingestion and the bioaccumulation of these microplastics in BSF larvae seem to be dependent on initial particle load, larval mouth size, and consequently on larval age (Lievens et al., 2023a).

Given the diversity of microplastics that can be found in the environment, it is now necessary to expand on these initial results, firstly by studying a wider spectrum of microplastic sizes and shapes, and secondly by developing mathematical models that can simulate various practical cases while limiting animal experiments. Indeed, while biowaste potentially used as substrates for industrial BSF larvae rearing may contain very heterogeneous microplastics, no study has yet addressed the combined impact of the size and shape of these microplastics on the production of larvae subsequently used as feed and the associated risk if they enter the food chain. To close this research gap and to enhance the risk assessment associated with the presence of different microplastics in food waste used for insect-based bioconversion, this research was performed. The aim of this study was to determine the impact of different microplastic sizes and shapes on BSF larval growth, while monitoring the microplastic ingestion, egestion and bioaccumulation. The study focused on polyethylene, which accounts for 34 % of the total plastics market, and is one of the most widely used types of polymer for food packaging (Golwala et al., 2021, Matthews et al., 2021). In the first part of this study, three different sizes of spherical fluorescent blue-labelled microplastics were spiked in an artificial food waste and their ingestion and egestion dynamics of the BSF larvae were investigated. In the second part, self-produced fluorescently labelled irregularly shaped microplastics were used to simulate realistic microplastics that can be found in biowaste. The impact of the shape on the ingestion and egestion dynamics by BSF larvae was assessed, in order to identify whether certain microplastics might be more problematic than others in the BSF larvae biowaste recycling sector. Finally, to extrapolate these results to other conditions, such as other microplastic sizes, while avoiding the multiplication of animal experiments, which today raise ethical and animal welfare issues, a kinetic model was developed for the first time to describe the concentration of microplastics in BSF larvae throughout the rearing and starvation periods as a function of particle size and shape.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microplastic production and characterization

2.1.2. Irregular microplastics

2.1.2.3. Characterization

The particle-size distribution of produced microplastics was measured using a laser diffraction particle size analyzer (Mastersizer 3000, Malvern Instruments Ltd, Worcestershire, U.K.). Microplastics were suspended in ethanol and stirred at 3100 rpm (Technisolv, VWR International, Radnor, USA), until an obscuration of approximately 5 % was obtained. The particle size at 10 % (Dv10), 50 % (Dv50, median diameter), and 90 % (Dv90) of the volume distribution were obtained. Each measurement was carried out in triplicate. Similarly to the spherical particles, a Gaussian function was fitted to the obtained size distributions to apply the kinetic model generalized for normally distributed particles. The obtained standard deviation was larger than that of the purchased microspheres (Fig. S2, Table S2).

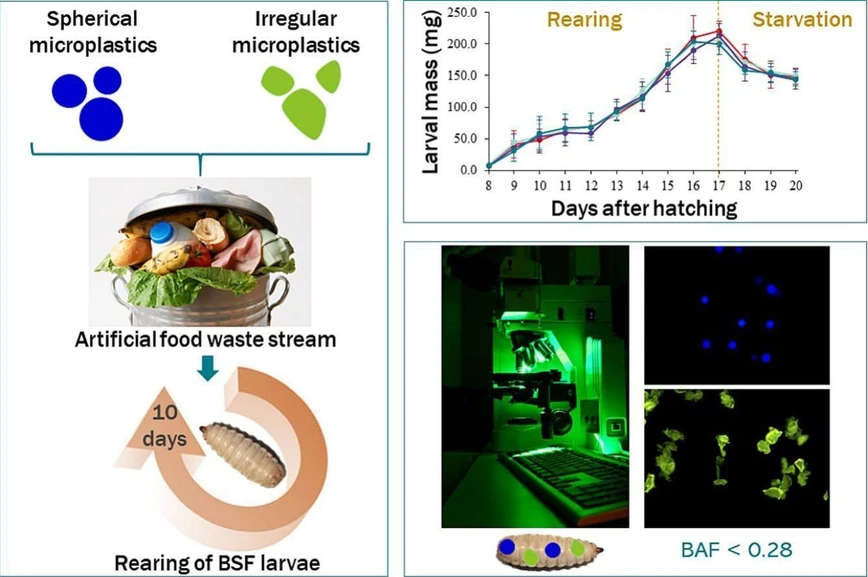

For the SEM analysis, the microplastics were placed on an aluminium stub and coated with a 5 nm-thick platinum-palladium layer using a high vacuum (turbomolecular pumped) coater (Q150T, Quorum). The SEM images were then produced at 5 kV acceleration voltage with a CBS (concentric backscatter, BSE) detector in a Nova Nanosem 450 (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, USA), while all other parameters like magnification, working distance (WD) and horizontal field width (HFW) are displayed on the respective image.

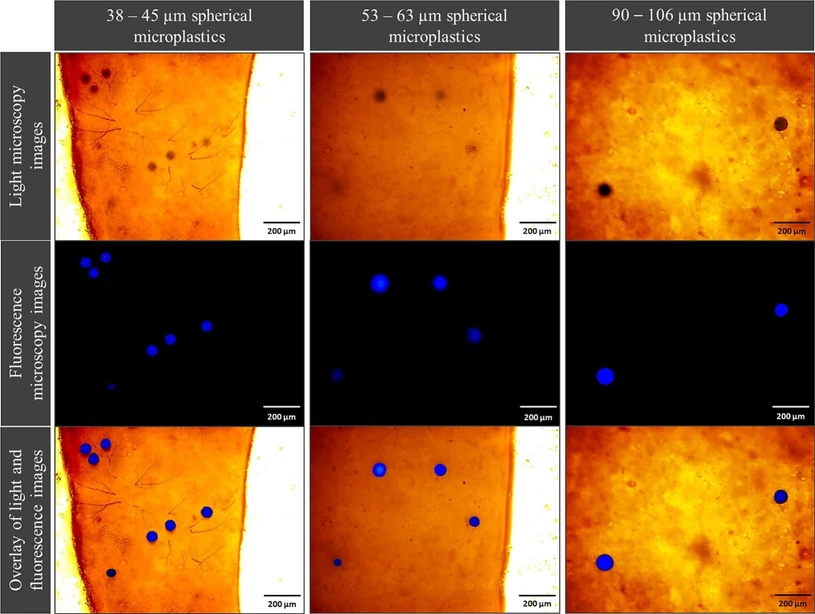

2.5. Microplastic visualization and quantification in larval guts

Microplastics were visualized in the lumen of larval guts using a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Axioplan, Germany) equipped with a MoticamPro 252A camera (Motic, Hong Kong). The fluorescent microscope featured a halogen lamp with a 96 HE BFP or a 09-filter set (VWR, USA) for the spherical and irregular microplastics respectively. The specific filter set used determines both excitation and emission wavelengths, with values of 450 – 490 nm (09-filter) and 340 – 390 nm (96 HE BFP), and 515 nm (09-filter) and 440 – 450 nm (96 HE BFP), respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Confirmation of the size and structure of the self-produced microplastics

The mean particle sizes of irregularly shaped microplastics are 67.9 µm, 89.8 µm, and 129 µm, respectively for the 45 – 75 µm, 75 – 106 µm, and 106 – 150 µm size ranges (Table S2). The size distribution of these irregular particles is slightly asymmetric with more large particles compared to a Gaussian distribution (Fig. S2).

Staining the particles had a negligible effect on their erratic shapes (Fig. 1 and Fig. S3). However, it was observed that the edges of the particles became less sharp and grainy for all size fractions. This is probably because of the staining process used, which might first induce swelling of the polymer, resulting in a slightly smoother surface.

Waste Management, 203, 2025, 114852: Fig. 1. SEM images (magnification: 1000 × ) of self-produced polyethylene microplastics before (left) and after (right) the application of the staining procedure. Size range fraction of the microplastics shown is 45 – 75 µm.

Waste Management, 203, 2025, 114852: Fig. 1. SEM images (magnification: 1000 × ) of self-produced polyethylene microplastics before (left) and after (right) the application of the staining procedure. Size range fraction of the microplastics shown is 45 – 75 µm.

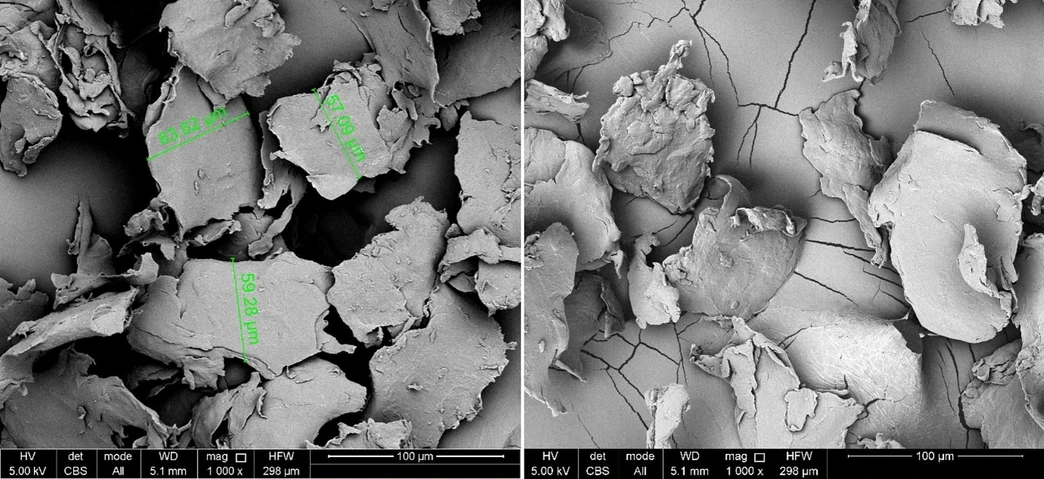

3.2. Overall larval growth on microplastic contaminated substrates

When looking at the effect of both spherical and irregularly shaped microplastics, no significant difference was observed between the weight of larvae reared on control or spiked substrate (p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA) (Fig. 2). The presence of polyethylene microplastics in the substrate has therefore no impact on the growth of BSF larvae. On average, the larval weight increased from 11.0 ± 3.7 mg to 221.4 ± 16.5 mg during rearing on substrate, while starvation resulted in an average larval weight reduction of 30.5 %.

Waste Management, 203, 2025, 114852: Fig. 2. Daily average weight (mg) of BSF larvae reared on an artificial food waste: (a) control (unspiked), spiked with spherical microplastics of three size ranges (38 – 45 µm; 53 – 63 µm; 90 – 106 µm), and (b) spiked with irregularly shaped microplastics of three size ranges (45 – 75 µm; 75 – 106 µm; 106 – 150 µm). A starvation phase was carried out between 17 and 20 days after hatching (DAH). Data points and error bars represent the mean value (9 repetitions) and the standard deviation, respectively.

Waste Management, 203, 2025, 114852: Fig. 2. Daily average weight (mg) of BSF larvae reared on an artificial food waste: (a) control (unspiked), spiked with spherical microplastics of three size ranges (38 – 45 µm; 53 – 63 µm; 90 – 106 µm), and (b) spiked with irregularly shaped microplastics of three size ranges (45 – 75 µm; 75 – 106 µm; 106 – 150 µm). A starvation phase was carried out between 17 and 20 days after hatching (DAH). Data points and error bars represent the mean value (9 repetitions) and the standard deviation, respectively.

3.3. Impact of spherical microplastic size on ingestion and egestion by BSF larvae

The blue-labelled particles observed under the fluorescence microscope (Fig. 3) remained spherical throughout the whole experiment. Regarding their number in the guts of BSF larvae, a significant difference can be observed at the end of the rearing period between the three different spherical particle sizes (Fig. 4). On average, 1725 ± 397, 555 ± 384 and 19 ± 13 particles were counted for the 38 – 45 µm, 53 – 63 µm and 90 – 106 µm size ranges, respectively (Table S1). For 38 – 45 µm and 53 – 63 µm spherical particles, an increase in the number of microplastics in the larval gut was observed from 9 DAH and 13 DAH, respectively. In contrast, for 90 – 106 µm spherical particles, the number of particles in the larval gut remains low (less than 20 particles) throughout the rearing experiment.

Waste Management, 203, 2025, 114852: Fig. 3. Light microscopy images, fluorescence microscopy images and overlay of both images of three size ranges (38 – 45 µm, 53 – 63 µm, 90 – 106 µm) of spherical blue marked polyethylene microplastics found in the guts of BSF larvae (magnification: 10 × ).

Waste Management, 203, 2025, 114852: Fig. 3. Light microscopy images, fluorescence microscopy images and overlay of both images of three size ranges (38 – 45 µm, 53 – 63 µm, 90 – 106 µm) of spherical blue marked polyethylene microplastics found in the guts of BSF larvae (magnification: 10 × ).

Waste Management, 203, 2025, 114852: Fig. 4. Number of polyethylene particles found in the guts of BSF larvae reared on an artificial food waste: control (unspiked), spiked with spherical polyethylene microplastics of three size ranges (38 – 45 µm, 53 – 63 µm, 90 – 106 µm), and spiked with irregularly shaped polyethylene microplastics of three size ranges (45 – 75 µm, 75 – 106 µm, 106 – 150 µm). A starvation stage was carried out between 17 and 20 days after hatching (DAH). Data points and error bars represent the mean value (9 repetitions) and the standard deviation, respectively.

Waste Management, 203, 2025, 114852: Fig. 4. Number of polyethylene particles found in the guts of BSF larvae reared on an artificial food waste: control (unspiked), spiked with spherical polyethylene microplastics of three size ranges (38 – 45 µm, 53 – 63 µm, 90 – 106 µm), and spiked with irregularly shaped polyethylene microplastics of three size ranges (45 – 75 µm, 75 – 106 µm, 106 – 150 µm). A starvation stage was carried out between 17 and 20 days after hatching (DAH). Data points and error bars represent the mean value (9 repetitions) and the standard deviation, respectively.

4. Discussion

4.5. Study limitations and future directions

Although our study provides relevant insights regarding the impact of microplastic size and shape on their ingestion and egestion by black soldier fly larvae during industrial biowaste recycling, it remains a proof-of-concept study carried out at lab-scale. These results will need to be validated on a larger scale, such as industrial conditions. Large-scale validation will also enable the model developed in this study to be refined in the future. In addition, this study needs to be complemented by further studies exploring potential biological effects, such as the impact of microplastics on the larval gut microbiota or on a potential inflammatory response. It is noteworthy that the protocol optimized in this study for staining irregular microplastics was effective in tracking microplastics in the guts of BSF larvae throughout the experiment, while having a negligible effect on the irregular particle shapes. This protocol relies on thermal expansion and contraction properties of microplastics and includes several rinsing steps. Given that Lv et al. (2019) observed that, based on SEM images, there was no significant change in the surface morphology of microplastics after heat treatment (30 min at 75 °C), the changes observed in our study could be linked to the rinsing steps applied. The latter were however of crucial importance to avoid subsequent leaching of the dye into the substrate. In the future, the effect of the staining protocol could be clarified by using atomic force microscopy (AFM) measurements to specify the surface roughness of stained microplastics, which is critical with regard to the carrying effect of pollutants by microplastics. In the meantime, the results obtained in the present study should be extrapolated with great caution to even sharper microplastics that could be found in biowaste used as substrate for BSF larvae rearing. Finally, an assessment of the microplastic content of the frass recovered after rearing BSF larvae on biowaste was not carried out in this study, but will be important in the future. Indeed, this frass could be used as a fertilizer, but this use must not lead to further contamination of soils with microplastics, particularly agricultural soils, for which recent French data have already revealed concentrations of up to 80 particles per kg of dry soil (Palazot et al., 2024).

5. Conclusion

As already observed in preliminary studies, this small-scale study confirmed that, in the case of industrial rearing of BSF larvae on biowaste, the presence of microplastics has no impact on their growth, whatever their size or shape. Moreover, kinetic modelling has shown that the shape of the particles may slightly modify the kinetic parameters of ingestion without having any final effect on the microplastic bioaccumulation in larval guts. Although there is no microplastic bioaccumulation in larvae during rearing (BAF < 0.3), the ingestion of small particles is significantly higher than that of large particles. Therefore, while large particles do not seem to be an issue for insect-based bioconversion, it would be interesting to study the fate of even smaller plastic particles (< 20 µm) that could be ingested early and easily by BSF larvae, and potentially transfer through membrane tissue. In order to better assess the risk associated with the presence of these plastic particles in larval rearing substrate, future research is required, not only to study the impact of chronic exposure to successive generations of larvae, but also to monitor the fate of these particles throughout the food chain if the larvae are used as feed, and their correlated potential health effects.