Coffee Silver Skin: A Useful Adsorbent Substrate for Norfloxacin Removal and Photodegradation

ACS Phys. Chem Au 2025, 5, 4, 375–386: Graphical abstract

This study explores Coffee Silver Skin, a coffee production by-product, as an adsorbent substrate for removing the antibiotic Norfloxacin from water. Adsorption occurred mainly through electrostatic interactions. Regeneration of the material was tested using advanced oxidation processes, particularly UV-based methods.

The best results were achieved with UV light/TiO₂, which enabled complete degradation of Norfloxacin within 6 hours, while H₂O₂ alone was not effective. A combined desorption–photodegradation approach in MgCl₂ solution further reduced irradiation time, achieving full degradation in 3 hours. Coffee Silver Skin demonstrated potential for reuse up to three cycles, supporting its role as a sustainable solution for antibiotic removal from water.

The original article

Coffee Silver Skin: A Useful Adsorbent Substrate for Norfloxacin Removal and Photodegradation

Domenico Cignolo, Vito Rizzi, Maria Teresa Bozzelli, Paola Fini, Andrea Petrella, Pinalysa Cosma, and Jennifer Gubitosa*

ACS Phys. Chem Au 2025, 5, 4, 375–386

https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphyschemau.5c00013

licensed under CC-BY 4.0

Selected sections from the article follow. Formats and hyperlinks were adapted from the original.

Antibiotics are the most frequently prescribed drugs worldwide, with a continuous increase in their usage, which has worsened the problem related to antibiotic resistance. Their large consumption is not limited to medicine; rather, they are employed also in dentistry, veterinary, and agriculture. (1) Among antibiotics, the large use of fluoroquinolones (FQs) is highlighted due to their broad-spectrum action against various pathogenic bacteria. Indeed, in the last years, their usage has increased for handling pneumonia in patients affected by SARS-CoV-2. (2) In this regard, Norfloxacin (NOR) is worth mentioning. (3) It is usually employed to treat urinary infections and prostate-related problems, both in hospital and veterinary fields, with an annual consumption of several tons, leading to being considered among the five most used antibiotics around the world. (4) Due to these large uses, NOR is commonly retrieved in water, being discharged from the effluents of hospitals, veterinary clinics, and domestic sources, and it has been detected in concentrations of μg/L or mg/L in sewage, groundwater, and surface water. However, this large presence can be toxic for humans, causing seizures, angioedema, peripheral neuropathy, tendon rupture, hallucinations, vomiting, nausea, diarrhea, hypersensitivity reactions, photosensitivity, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, and effects on the central nervous system. Moreover, it can lead to toxic effects on aquatic ecosystems, damaging them to a huge extent. (4) On these bases, NOR has been classified as a Contaminant of Emerging Concern (CEC), and it raises the need to remove this pollutant from water. (5) For this purpose, many techniques have already been explored, i.e., filtration, reverse osmosis, adsorption, coagulation–flocculation, ion exchange, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), and biological wastewater treatments. (6−10) However, the use of some of these approaches is not strongly encouraged, exhibiting disadvantages, such as the cost of installation, chemical reagents, energy requirement, production of a high volume of sludge, or low efficiency and long required times. (11) On the other hand, the use of adsorption and degradation processes (especially devoted to photodegradation involving UV light, assisted by photocatalyst or oxidant agent, Fenton-like processes, persulfate-based advanced oxidation processes, and ionizing or γ-ray irradiation) could be considered the most prominent techniques for NOR removal. (4,11−22)

Differently, this work aimed to adsorb and then photodegrade NOR at the solid state for successfully regenerating the adsorbent, extending its lifetime. At the same time, the proposed approach enabled the possibility of destroying NOR under controlled conditions, avoiding the unwanted release of other substances into water. Specifically, Coffee Silver Skin (CSS) was adopted as an adsorbent substrate. The CSS is the thin skin covering the green coffee bean, representing the by-product obtained from roasting green coffee berries. It is collected in large amounts from the roasting factories. (26−28) However, although the Circular Economy principles encourage the use of by-products for their valorization, simultaneously lowering the environmental impact, (29,30) the reuse of CSS for different applications has not been fully explored. It has been mainly used as biomass or for the extraction of bioactive molecules, with the perspective of developing systems to obtain feed, fertilizer, microbial fermentation materials for biorefinery, and the recovery of energy by combustion. (26,31,32) On the other hand, considering its potential application for water remediation, many studies have been devoted to the general use of coffee waste, also in the form of active carbon, to remove different pollutants, (33−35) while the use of CSS has not been widely contemplated. Interestingly, Malara et al. proposed CSS as an adsorbent material to remove heavy metals. (36) Based on this background, this work contributes to suggesting a way for further valorizing CSS, using this biomass for water remediation to remove CECs, and recycling it through AOPs. Moreover, unlike similar works in the field, hard experimental conditions for pretreating CSS before its use as an adsorbent were avoided, proposing only the use of hot water, further lowering the environmental impact. (37,38) Furthermore, it is important to highlight that, regarding the use of coffee wastes in NOR removal, only biochar derived from spent coffee grounds (35) and coffee husk (38) have been reported for NOR adsorption, highlighting the importance of the present work. To get insight into the NOR’s degradation, both in solid state on CSS or when released from the adsorbent and destroyed, a comparison with the well-known (19,21,39) NOR degradation in water solution was performed, unveiling the retrieved results. New horizons are thus opened with this work, showing in the literature a valid way to regenerate CSS, extending its use, according to sustainability principles.

1. Experimental Section

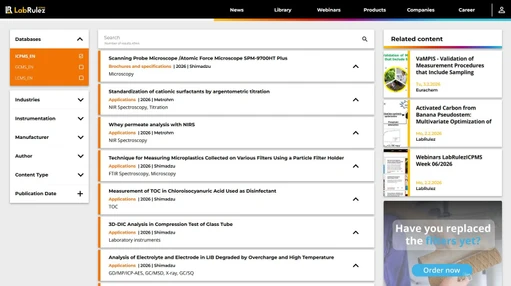

1.3. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy Analyses

A Fourier transform infrared spectrometer, Shimadzu IRXross, Shimadzu Corp., was adopted to collect the ATR-FTIR spectra of CSS before and after photodegradation processes in the range of 500–4000 cm–1. In particular, the dried samples were placed on the ATR crystal and pressed down using the swivel press to ensure optimal contact between the sample and the crystal. A constant strength was used for each analysis. A resolution of 4 cm–1 was set, and 45 scans were summed for each acquisition.

1.4. Thermogravimetric Analyses (TGAs)

The thermal investigation of the adsorbent was performed using a thermogravimetric instrument (PerkinElmer Pyris 1), and analyses were performed under an inert atmosphere using nitrogen as a purge gas with a constant flow rate of 20 mL/min. Each sample was heated from 30 to 650 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min.

1.5. UV–vis Analyses

A Shimadzu UV-2600i UV–vis-NIR spectrophotometer was employed for monitoring the adsorption, desorption, and photodegradation processes. The UV–vis spectra of NOR solutions were acquired at different time intervals in the wavelength range 200–450 nm, at a 1 nm/s scan rate.

1.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analyses

The morphology of the adsorbent samples was investigated using a Zeiss scanning electron microscope model EVO50XVP (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany). The samples were fixed on aluminum stubs with colloidal graphite and then sputtered with a 30 nm thick carbon film using an Edwards Auto 306 thermal evaporator. SEM operating conditions were an accelerating potential of 15 kV and a probe current of 500 pA.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1.1. SEM Analysis

Macroscopically, raw CSS and CSS washed with water appeared as sawdust, having a yellowish color, with a smooth and compacted surface (see the camera picture reported in Figure 2A). In detail, SEM analyses revealed that raw CSS had a rough and heterogeneous surface made of flakes, characterized by cracks and covered by some impurities (Figure 2C,D). At the same time, according to the sampling regions (Figure 2C,D), they exhibited a wrinkled structure with an irregular surface with grooves, channeling, cracks, and nodules. After washing with water, the whole irregular morphology of CSS was retrieved, but the treatment compacted the structure due to a novel arrangement of the CSS network. Specifically, more characteristics can be appreciated in Figure 2E,F, confirming the findings. Indeed, the use of water for washing the biomass-based adsorbent should remove impurities, not affecting the entire characteristics of the material.

ACS Phys. Chem Au 2025, 5, 4, 375–386: Figure 2. Camera picture of water-washed CSS (A), Norfloxacin molecular structure (B), and SEM images of raw CSS (C, D), water-washed CSS at different magnification ratios (E, F), and recycled CSS at different magnification ratios (G, H).

ACS Phys. Chem Au 2025, 5, 4, 375–386: Figure 2. Camera picture of water-washed CSS (A), Norfloxacin molecular structure (B), and SEM images of raw CSS (C, D), water-washed CSS at different magnification ratios (E, F), and recycled CSS at different magnification ratios (G, H).

2.1.2. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy Analyses

ATR-FTIR was performed to reveal the main functional groups on the CSS surface (Figure 3). According to other studies, the ATR-FTIR spectra showed the characteristic signals of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. (40,41) Specifically, starting from raw CSS, the peak observed at 3315 cm–1 was associated with the O–H stretching of lignin phenols and the hydroxyl groups of cellulose and hemicellulose monosaccharides. The presence of two weak bands at 2918 and 2847 cm–1 was due to the symmetric and asymmetric stretching of the C–H bonds in the three polymers. The strong band at 1635 cm–1 and the weak peak at 1765 cm–1 could be ascribed to C═O vibrations of ketones, aldehydes, esters, and carboxylic acids. (42,43) Moreover, these signals could be correlated to the presence of other compounds, such as caffeine and chlorogenic acid. (40)

ACS Phys. Chem Au 2025, 5, 4, 375–386: Figure 3. ATR-FTIR spectra (in the range between 4000 and 400 cm–1) of raw CSS (black line), washed CSS (red line), CSS after NOR adsorption (green line), and CSS recycled for three adsorption and photodegradation cycles (blue line).

ACS Phys. Chem Au 2025, 5, 4, 375–386: Figure 3. ATR-FTIR spectra (in the range between 4000 and 400 cm–1) of raw CSS (black line), washed CSS (red line), CSS after NOR adsorption (green line), and CSS recycled for three adsorption and photodegradation cycles (blue line).

Specifically, starting from raw CSS, the peak observed at 3315 cm–1 was associated with the O–H stretching of lignin phenols and the hydroxyl groups of cellulose and hemicellulose monosaccharides. The presence of two weak bands at 2918 and 2847 cm–1 was due to the symmetric and asymmetric stretching of C–H bonds in the three polymers. The strong band at 1635 cm–1 and the weak peak at 1765 cm–1 could be ascribed to C═O vibrations of ketones, aldehydes, esters, and carboxylic acids. (42,43) Moreover, these signals could be correlated to the presence of other compounds, such as caffeine and chlorogenic acid. (40) The peaks at 1550–1200 cm–1 could include the C═C vibration in the aromatic ring of lignin (43) and the vibration modes of −CH3, −CH2–, −CH– from cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, without excluding the involvement of C–O stretching of ether, phenol, and ester of lignin. (44) Lastly, the strong band at 1027 cm–1 and the shoulder at 1108 cm–1 could be due to the −C–O–C– vibration of glycosidic bonds between monosaccharides in cellulose and hemicellulose. (41) After the treatment of CSS with water, the ATR-FTIR spectrum appeared to be affected according to SEM analysis. In particular, the ratio intensity between the signals at 1745 cm–1 and 1635 cm–1 changed, showing an increase of the former, which appeared to be well-defined, and a reduction of the latter. At the same time, some variations were appreciated in the range 1425–1200 cm–1. Therefore, by considering other similar studies reported in the literature, (45) the findings could indicate a rearrangement of the CSS network, involving a new assembly of the biopolymer chains after water washing. (46)

2.1.3. Thermogravimetric Analyses

In excellent agreement with other works, (40,41,47,48) TGA curves of the investigated samples presented the typical signals of lignocellulosic materials (Figure 4A).

ACS Phys. Chem Au 2025, 5, 4, 375–386: Figure 4. TGA (A) and related DTG curves (B) of raw CSS (black line); CSS washed with hot water (red line); CSS after NOR adsorption (green line); and CSS recycled for three adsorption and photodegradation cycles (blue line).

ACS Phys. Chem Au 2025, 5, 4, 375–386: Figure 4. TGA (A) and related DTG curves (B) of raw CSS (black line); CSS washed with hot water (red line); CSS after NOR adsorption (green line); and CSS recycled for three adsorption and photodegradation cycles (blue line).

The raw CSS showed the first thermal event starting at 50–60 °C. It consisted of losing around 5% of the weight, and it could be correlated with the evaporation of surface-bound water. (40,47,48) Conversely, the most significant weight loss of 50% between 200 and 400 °C should involve the degradation of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. (40,41) These weight losses characterized the corresponding Differential Thermogravimetric (DTG) curves (Figure 4B), causing the main broadband at 334 °C, with a less significant weight loss evidenced with a shoulder at 270 °C. Then, in the TGA curves at temperatures greater than 400 °C, 15% of the mass was lost, and the finding was attributed to lignin degradation. (42) At 650 °C, a residual mass of 30% was not degraded, and the signal could be assigned to the presence of nonburned inorganic compounds. (48)

After washing with water, the main CSS degradation stages started at higher temperatures, particularly at 230 °C, with a slight increase in weight loss to 60% (Figure 4A). At the same time, the maximum in the DTG curve of the observed broad signal shifted to 368 °C (Figure 4B). A similar behavior was observed in the literature, suggesting the reorganization of biopolymers in a new assembly, altered by the use of water, leading to an adsorbent more thermally stable if compared with raw CSS. (49−54) For instance, Benìtez-Guerrero et al. (55) correlated the increase in thermal stability of another biomass, washed with hot water, to a better packing of the cellulose. Not surprisingly, the compacted morphology observed during the SEM investigation confirmed this result.

3. Conclusions

This work aims to valorize Coffee Silver Skin, a by-product of coffee torrefaction, as an adsorbent material for the removal of Norfloxacin from water. In particular, the recycling of the adsorbent with AOPs was successfully performed. The CSS was preliminarily characterized by using SEM, ATR-FTIR, and TGA, inferring information about its heterogeneous and rough surface and the lignocellulosic composition. For the CSS recycling, the application of different UV-light-based AOPs was investigated to photodegrade the adsorbed NOR; the addition of TiO2 in the solution containing the adsorbent favored the process, whereas the use of H2O2 hindered the process. A comparison with the NOR behavior when irradiated directly in water was thus performed to gain information about the proposed degradation on the CSS surface in the solid state. With the aim of reducing the exposure times to UV light, the NOR photodegradation was exploited during its release from CSS, thanks to the addition of 0.1 M MgCl2. This procedure demonstrated not only the possibility of adsorbing the pollutant but also proposed a simple way to desorb the adsorbed NOR from CSS through the use of an electrolyte. Therefore, after exposing loaded CSS to UV light for 3 h in the electrolyte solution and in the presence of TiO2, 80% of adsorbed NOR was photodegraded. The process could be improved by adding H2O2 to the water solution at a concentration of 0.1 M, allowing complete photodegradation of the antibiotic. However, to avoid the use of strong oxidative conditions, the use of UV/TiO2 and a MgCl2 solution was chosen as an approach to recycling CSS for various adsorption/photodegradation cycles. Although SEM, ATR-FTIR, and TGA showed an alteration of adsorbent material after the recycling step due to the oxidative medium of the lignocellulosic material, the adsorption performance remained the same, allowing us to consider this system suitable for removing NOR from water. In summary, CSS could be used to adsorb NOR from water and induce photodegradation in the solid state, avoiding the direct degradation of pollutants in water with the release of undesired by-products; thus, better control of the photodegradation treatment should be obtained.