Structural Characterization and Multiomics Analysis Reveal Extensive Diversity and Global Distribution of Kurstakin Lipopeptides

J. Nat. Prod. 2025, 88, 12, 2960–2967: Graphical abstract

Bacillus species produce diverse bioactive lipopeptides that contribute to their ecological and biocontrol functions, yet some families remain poorly characterized. This study focuses on kurstakins, a lipopeptide family associated with biocontrol activity, using metabolomic, structural, and multiomics approaches.

Metabolomic analysis of a Bacillus cereus extract revealed approximately 50 kurstakin analogs with diverse linear and branched lipid tails. Two new analogs were isolated and fully characterized by NMR, providing the first experimental determination of absolute configuration within this family. Integration of public genomic and MS data further demonstrated the broad chemical diversity and global distribution of kurstakins, highlighting their potential ecological significance in Bacillus-based biocontrol systems.

The original article

Structural Characterization and Multiomics Analysis Reveal Extensive Diversity and Global Distribution of Kurstakin Lipopeptides

Rose Campbell, and Emily Mevers*

J. Nat. Prod. 2025, 88, 12, 2960–2967

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5c01212

licensed under CC-BY 4.0

Selected sections from the article follow. Formats and hyperlinks were adapted from the original.

Lipopeptides are a well-known family of microbial natural products that possess a range of applications, including their potential medicinal uses and as crop biocontrol agents. (1) Several lipopeptides or synthetic analogs are FDA-approved for the treatment of infectious diseases, including as antibiotics (e.g., polymyxin B, oritavancin, telavancin, and daptomycin) and antifungals (e.g., rezafungin and micafungin), with many others in various stages of clinical trials. (2,3) Their bioactive properties arise from their amphiphilic structures, which consist of a fatty acid tail (lipid) and a polar peptide. The lipopeptide antibiotics are known to bind to cell membranes, forming pores that lead to depolarization. (4) Lipopeptides are commonly produced by a diverse range of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and cyanobacteria; however, Bacilli are particularly well-known for their ability to produce structurally diverse bioactive lipopeptides. This includes the widespread production of surfactins, iturins, fengycins, polypeptins, and octapeptins. (2,5) This biosynthetic capability has led to their wide use as biocontrol agents in agricultural settings, such as Bacillus thuringiensis being leveraged for insect and disease control and Bacillus velezensis for controlling plant pathogens. (6,7) The diverse lipopeptides produced by these strains have been shown to work synergistically as antifungals, biofilm formation regulators, and plant defense modulators. (5,8)

Although many lipopeptides have been well characterized from Bacilli, this does not represent their full biosynthetic potential. (9) In addition, many lipopeptide families have been mentioned in the literature, but lack appropriate analytical data to confirm their planar and secondary structures and the diversity of the family. (2) This includes the kurstakins, gavaserin, and saltavalin, which have all been implicated to play a critical role in the biocontrol properties of the producing organisms. (10) The kurstakins were first discovered to be produced by B. thuringiensis, and have been considered a biomarker for Bacillus cereus group species. (11,12) However, they have since been isolated from a range of bacteria, including non-cereus group Bacillus species (e.g., B. subtilis, B. licheniformis) (13,14) and more distantly related bacteria (e.g., Enterobacter cloacae, and Citrobacter sp.). (15,16) Several of the producing strains have been studied extensively for their potential use as a biocontrol agent, due to their antimicrobial activity and ability to swarm and produce protective biofilms, (12,17,18) which has been attributed in part to the kurstakins. (19−22) Four cyclic analogs, kurstakins 1–4 (1–4), were elucidated through tandem mass spectrometry (MSMS) analyses and chemical derivatization. (12) There have been reports of many additional analogs, but these reports are primarily based on MS analyses. (23−25) The studies indicate that all analogs contain the same peptide core, but incorporate diverse lipid tails. Additionally, amino acid configurations were deduced through bioinformatic analyses alone, (17) which can only predict the configuration of the α-position. Therefore, chemical analyses are needed to unequivocally determine the amino acid configurations, particularly of the β-hydroxyl in the threonine residue. Herein, we leveraged our metabolomic data set from marine bacteria to characterize the kurstakins, including the first NMR analysis, report of two new analogs, kurstakins 5 and 6 (5–6), deduction of the absolute configuration, and analysis of the true chemical diversity and distribution of the kurstakins.

Results and Discussion

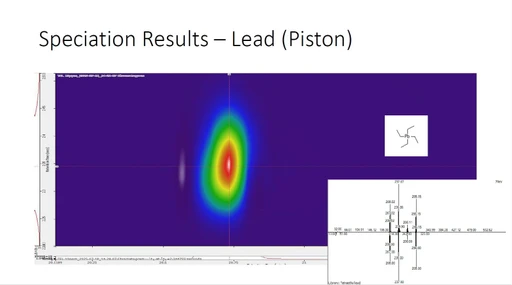

Analysis of a Global Natural Product Social (GNPS) molecular network representing the chemical potential of diverse marine bacteria from our internal library revealed that it contained a rather large spectral family, with masses ranging from 850 to 940 m/z (Figure 1A). (26) A subset of these nodes were identified as 1–4 based on their exact mass and key fragment ions (Figure 1B). A peak at 110.1 m/z, which putatively represents a decarboxylated histidine, was abundant in all MSMS spectra and became a key identifying fragment (Figure S1). Other nodes matched masses of reported kurstakin analogs with hypothetical structures, (15,19,23,27) as well as new analogs. Based on key MS fragments, this spectral family represents both cyclic and linear core peptide sequences that have incorporated various lipid tails (e.g., C9–C14 with and without hydroxylation; Figure S2–S3).

J. Nat. Prod. 2025, 88, 12, 2960–2967: Figure 1. (A) Molecular family of kurstakins found in the marine isolates library, showing structural diversity in tail structure and peptide linearity. (B) Key common fragments of each core peptide used to identify the kurstakins. Fragments not including histidine were rarely observed. (C) Overlaid EICs of all kurstakin masses observed in an enriched semipure fraction, 850–996 m/z, representing a large diversity of cyclic (aqua), linear (blue), and hydroxyl-tail (red) analogs.

J. Nat. Prod. 2025, 88, 12, 2960–2967: Figure 1. (A) Molecular family of kurstakins found in the marine isolates library, showing structural diversity in tail structure and peptide linearity. (B) Key common fragments of each core peptide used to identify the kurstakins. Fragments not including histidine were rarely observed. (C) Overlaid EICs of all kurstakin masses observed in an enriched semipure fraction, 850–996 m/z, representing a large diversity of cyclic (aqua), linear (blue), and hydroxyl-tail (red) analogs.

To characterize the structural breadth of the kurstakin family, the producing strain, B. cereus EM195W, was grown in large-scale (8 L) liquid media containing hydrophobic resins (HP-20, XAD4, and XAD7) to capture the secreted small molecules. After 9 days, the resin was extracted with organic solvents to generate a crude extract. The crude extract was first subjected to reverse-phase (RP) flash chromatography to yield eight refined fractions. MS analysis revealed that the kurstakins were present in the nonpolar fractions, which were combined and processed through normal-phase (NP) flash chromatography, generating an additional 13 fractions. Fractions that were highly enriched with the kurstakins were reanalyzed by high-resolution liquid chromatography-MS (HR-LCMS), revealing the presence of many more analogs than previously detected in the original GNPS analysis. Manual interpretation of the MS data indicated that there is significantly more tail variation than previously thought, which was likely overlooked due to the isobaric nature of many of the analogs and low relative abundance of several analogs (Figure 1C). In total, 31 masses ranging from 850–996 m/z were detected, representing approximately 50 distinct analogs (Table S1, Figure S4). The breadth of these analogs spanned tail lengths ranging from C9–C17, most of which appeared as all possible combinations of linear- or cyclic-peptide core with and without hydroxylated tails, and represented many previously undescribed compounds.

To discover the breadth of tail diversity, we turned to gas chromatography-MS (GC-MS) analysis. A portion of one of the semipurified NP fractions was treated with HCl (aq) to liberate the free acid, which was subsequently methylated with TMS-diazomethane. The methylated fatty acids were analyzed by GC-MS, comparing the retention times and fragmentation patterns with authentic standards of linear, iso-branched, and anteiso-branched fatty acid methyl esters (LCFA, iBCFA, and aBCFA, respectively). (34) Comparing the derivatized natural material to the LCFA standards revealed the presence of linear fatty acid tails ranging in length from C9–C18 (Figure 2A). This agreed with the masses found on the HR-LCMS, but with the addition of the C18 LCFA.

J. Nat. Prod. 2025, 88, 12, 2960–2967: Figure 2. Chemical characterization of the family of kurstakins. (A) GC-MS traces (EIC of common 74.1 m/z fragment) of the semipure B. cereus EM195W fraction (purple) compared to the LCFA (blue) and iBCFA (aqua) standards. (B) Summary of all fatty acid tails identified in kurstakins produced by EM195W.

J. Nat. Prod. 2025, 88, 12, 2960–2967: Figure 2. Chemical characterization of the family of kurstakins. (A) GC-MS traces (EIC of common 74.1 m/z fragment) of the semipure B. cereus EM195W fraction (purple) compared to the LCFA (blue) and iBCFA (aqua) standards. (B) Summary of all fatty acid tails identified in kurstakins produced by EM195W.

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotation data were recorded on a JASCO P-2000 polarimeter. NMR spectra were recorded in d6-DMSO with the residual solvent peak as an internal standard (δC 39.5, δH 2.50) on a Bruker Avance III 600 MHz instrument equipped with a triple resonance inverse (CP-TCI) Prodigy N2 cooled CryoProbe (1H 600 MHz; 13C 150 MHz) or a Bruker Avance II 500 MHz instrument equipped with a CPBBO Prodigy N2 cooled CryoProbe (1H 500 MHz; 13C 125 MHz). TFA fuming was monitored on a JEOL ECZ 400 MHz instrument equipped with a Royal HFX probe (1H 400 MHz). GC-MS data were obtained using an Agilent 5975C VL MSD GC-MS. LR-LCMS data were obtained using an Agilent 1200 series HPLC system equipped with a photodiode array detector and a Thermo LTQ mass spectrometer. HR-ESIMS and HR-MSMS were carried out using an Agilent 6530 Q-TOF equipped with a 1290 Infinity II UPLC system or a Thermo Orbitrap Exploris 120 mass spectrometer. Reverse-phase flash chromatography purification was carried out with a Biotage Selekt automated flash chromatography system. HPLC purifications were carried out using a 1260 Infinity II HPLC system equipped with a photodiode array detector. All solvents were of HPLC quality.